Relativity of simultaneity

In physics, the relativity of simultaneity is the concept that simultaneity—whether two events occur at the same time—is not absolute, but depends on the observer's reference frame. According to the special theory of relativity, it is impossible to say in an absolute sense whether two events occur at the same time if those events are separated in space. Where an event occurs in a single place—for example, a car crash—all observers will agree that both cars arrived at the point of impact at the same time. But where the events are separated in space, such as one car crash in London and another in New Delhi, the question of whether the events are simultaneous is relative: in some reference frames the two accidents may happen at the same time, in others (in a different state of motion relative to the events) the crash in London may occur first, and in still others the New Delhi crash may occur first.

If we imagine one reference frame assigns precisely the same time to two events that are at different points in space, a reference frame that is moving relative to the first will generally assign different times to the two events. This is illustrated in the ladder paradox, a thought experiment which uses the example of a ladder moving at high speed through a garage.

A mathematical form of the relativity of simultaneity ("local time") was introduced by Hendrik Lorentz in 1892, and physically interpreted (to first order in v/c) as the result of a synchronization using light signals by Henri Poincaré in 1900. However, both Lorentz and Poincaré based their conceptions on the aether as a preferred but undetectable frame of reference, and continued to distinguish between "true time" (in the aether) and "apparent" times for moving observers. It was Albert Einstein in 1905 who abandoned the (classical) aether and emphasized the significance of relativity of simultaneity to our understanding of space and time. He deduced the failure of absolute simultaneity from two stated assumptions:

- the principle of relativity—the equivalence of inertial frames, such that the laws of physics apply equally in all inertial coordinate systems;

- the constancy of the speed of light detected in empty space, independent of the relative motion of its source.

Contents |

The train-and-platform thought experiment

A popular picture for understanding this idea is provided by a thought experiment consisting of one observer midway inside a speeding traincar and another observer standing on a platform as the train moves past. It is similar to thought experiments suggested by Daniel Frost Comstock in 1910[1] and Einstein in 1917[2][3].

A flash of light is given off at the center of the traincar just as the two observers pass each other. The observer onboard the train sees the front and back of the traincar at fixed distances from the source of light and as such, according to this observer, the light will reach the front and back of the traincar at the same time.

The observer standing on the platform, on the other hand, sees the rear of the traincar moving (catching up) toward the point at which the flash was given off and the front of the traincar moving away from it. As the speed of light is finite and the same in all directions for all observers, the light headed for the back of the train will have less distance to cover than the light headed for the front. Thus, the flashes of light will strike the ends of the traincar at different times.

Spacetime diagrams

It may be helpful to visualize this situation using spacetime diagrams. For a given observer, the  -axis is defined to be a point traced out in time by the origin of the spatial coordinate

-axis is defined to be a point traced out in time by the origin of the spatial coordinate  , and is drawn vertically. The

, and is drawn vertically. The  -axis is defined as the set of all points in space at the time

-axis is defined as the set of all points in space at the time  =0, and is drawn horizontally. The statement that the speed of light is the same for all observers is represented by drawing a light ray as a 45° line, regardless of the speed of the source relative to the speed of the observer.

=0, and is drawn horizontally. The statement that the speed of light is the same for all observers is represented by drawing a light ray as a 45° line, regardless of the speed of the source relative to the speed of the observer.

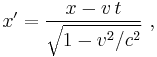

In the first diagram, we see the two ends of the train drawn as grey lines. Because the ends of the train are stationary with respect to the observer on the train, these lines are just vertical lines, showing their motion through time but not space. The flash of light is shown as the 45° red lines. We see that the points at which the two light flashes hit the ends of the train are at the same level in the diagram. This means that the events are simultaneous.

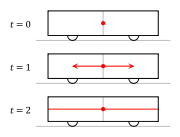

In the second diagram, we see the two ends of the train moving to the right, shown by parallel lines. The flash of light is given off at a point exactly halfway between the two ends of the train, and again form two 45° lines, expressing the constancy of the speed of light. In this picture, however, the points at which the light flashes hit the ends of the train are not at the same level; they are not simultaneous.

The dashed grey line between the events of the light beams hitting the ends of the trains identifies a volume of simultaneity for the observer on the train, i.e. those events which he calculates occur at the same instant of time (these form a flat 3-dimensional surface). Note that for the observer on the platform, each point on that line (identifying a plane where y and z coordinates are the same) is on a different level. So each point on that dashed grey line exists at a different time for the station observer, and at the same time for the observer on the train. That is the essence of the relativity of simultaneity.

Lorentz transformations

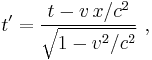

The relativity of simultaneity can be calculated using Lorentz transformations, which relate the coordinates used by one observer to coordinates used by another in uniform relative motion with respect to the first.

Assume that the first observer uses coordinates labeled  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  , while the second observer uses coordinates labeled

, while the second observer uses coordinates labeled  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  . Now suppose that the first observer sees the second moving in the

. Now suppose that the first observer sees the second moving in the  -direction at a velocity

-direction at a velocity  . And suppose that the observer's coordinate axes are parallel and that they have the same origin. Then, the Lorentz transformations show that the coordinates are related by the equations

. And suppose that the observer's coordinate axes are parallel and that they have the same origin. Then, the Lorentz transformations show that the coordinates are related by the equations

where  is the speed of light. If two events happen at the same time in the frame of the first observer, they will have identical values of the

is the speed of light. If two events happen at the same time in the frame of the first observer, they will have identical values of the  -coordinate. However, if they have different values of the

-coordinate. However, if they have different values of the  -coordinate (different positions in the

-coordinate (different positions in the  -direction), we see that they will have different values of the

-direction), we see that they will have different values of the  coordinate; they will happen at different times in that frame. The term that accounts for the failure of absolute simultaneity is that

coordinate; they will happen at different times in that frame. The term that accounts for the failure of absolute simultaneity is that  .

.

The equation t'=constant defines a "line of simultaneity" in the (x', t') coordinate system for the second (moving) observer, just as the equation t=constant defines the "line of simultaneity" for the first (stationary) observer in the (x, t) coordinate system. We can see from the above equations for the Lorentz transform that t' is constant if and only if  = constant. Thus the set of points that make t constant are different from the set of points that makes t' constant. That is, the set of events which are regarded as simultaneous depends on the frame of reference used to make the comparison.

= constant. Thus the set of points that make t constant are different from the set of points that makes t' constant. That is, the set of events which are regarded as simultaneous depends on the frame of reference used to make the comparison.

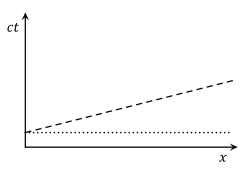

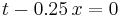

Graphically, this can be represented on a space-time diagram by the fact that a plot of the set of points regarded as simultaneous generates a line which depends on the observer. In the space-time diagram at the right, the dashed line represents a set of points considered to be simultaneous with the origin by an observer moving with a velocity v of one-quarter of the speed of light. The dotted horizontal line represents the set of points regarded as simultaneous with the origin by a stationary observer. This diagram is drawn using the (x, t) coordinates of the stationary observer, and is scaled so that the speed of light is one, i.e. so that a ray of light would be represented by a line with a 45 degree angle from the x axis. From our previous analysis, given that v = 0.25 and c = 1, the equation of the dashed line of simultaneity is  and with v=0, the equation of the dotted line of simultaneity is

and with v=0, the equation of the dotted line of simultaneity is  . It should also be mentioned that Lorentz came up with his ideas based on the assumption that the Aether existed.

. It should also be mentioned that Lorentz came up with his ideas based on the assumption that the Aether existed.

History

In 1892 and 1895, Hendrik Lorentz used a mathematical tool called "local time"  for explaining the negative aether drift experiments.[4] However, Lorentz gave no physical explanation of this effect. This was done by Henri Poincaré who already in 1898 emphasized the conventional nature of simultaneity and who argued that it is convenient to postulate the constancy of the speed of light in all directions. However, this paper does not contain any discussion of Lorentz's theory or the possible difference in defining simultaneity for observers in different states of motion.[5][6] This was done in 1900, when he derived local time by assuming that within the aether the speed of light is invariant. Due to the "Principle of relative motion" also moving observers within the aether assume that they are at rest and that the speed of light is constant in all directions (only to first order in v/c). So if they synchronize their clocks by using light signals, they will only consider the transit time for the signals, but not their motion in respect to the aether. So the moving clocks are not synchronous and do not indicate the "true" time. Poincaré calculated that this synchronization error corresponds to Lorentz's local time.[7][8] Also in 1904 Poincaré emphasized the connection between the principle of relativity, "local time", and light speed invariance, however, the reasoning in that paper was presented in a qualitative and conjectural manner.[9][10]

for explaining the negative aether drift experiments.[4] However, Lorentz gave no physical explanation of this effect. This was done by Henri Poincaré who already in 1898 emphasized the conventional nature of simultaneity and who argued that it is convenient to postulate the constancy of the speed of light in all directions. However, this paper does not contain any discussion of Lorentz's theory or the possible difference in defining simultaneity for observers in different states of motion.[5][6] This was done in 1900, when he derived local time by assuming that within the aether the speed of light is invariant. Due to the "Principle of relative motion" also moving observers within the aether assume that they are at rest and that the speed of light is constant in all directions (only to first order in v/c). So if they synchronize their clocks by using light signals, they will only consider the transit time for the signals, but not their motion in respect to the aether. So the moving clocks are not synchronous and do not indicate the "true" time. Poincaré calculated that this synchronization error corresponds to Lorentz's local time.[7][8] Also in 1904 Poincaré emphasized the connection between the principle of relativity, "local time", and light speed invariance, however, the reasoning in that paper was presented in a qualitative and conjectural manner.[9][10]

Albert Einstein in 1905 used a similar method to derive the time transformation for all orders in v/c, i.e. the complete Lorentz transformation (also Poincaré got the full transformation in 1905 but in those papers he did not mention his synchronization procedure). This derivation was completely based on light speed invariance and the relativity principle, so Einstein noted that for the electrodynamics of moving bodies the aether is superfluous. Thus the separation into "true" and "local" times of Lorentz and Poincaré vanishes - all times are equally valid and therefore the relativity of length and time is a natural consequence.[11][12][13] In 1908 Herman Minkowski used a quadratic form to present a primitive model of spacetime near a given event taken as the origin of a four-dimensional coordinate system. This model displays relativity of simultaneity through the concept of a simultaneous hyperplane that depends on the velocity of the traveler through the event.[14]

Einstein's train thought experiment

Einstein's version of the experiment[3] presumed slightly different conditions, where a train moving past the standing observer is struck by two lightnings simultaneously, but at different positions along the axis of train movement (back and front of the traincar). In the inertial frame of the standing observer, there are three events which are spatially dislocated, but simultaneous: event of the standing observer facing the moving observer (i.e. the center of the train), event of lightning striking the front of the traincar, and the event of lightning striking the back of the car.

Since the events are placed along the axis of train movement, their time coordinates become projected to different time coordinates in the moving train's inertial frame. Events which occurred at space coordinates in the direction of train movement (in the stationary frame), happen earlier than events at coordinates opposite to the direction of train movement. In the moving train's inertial frame, this means that lightning will strike the front of the traincar before two observers align (face each other).

References

- ↑ The thought experiment by Comstock described two platforms in relative motion. See: Comstock, D.F. (1910), "The principle of relativity", Science 31 (803): 767–772, doi:10.1126/science.31.803.767, PMID 17758464.

- ↑ Einstein's thought experiment used two light rays starting at both ends of the platform. See: Einstein A. (1917), Relativity: The Special and General Theory, Springer

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Einstein, Albert (2009). Relativity - The Special and General Theory. READ BOOKS. p. 30-33. ISBN 1-444-63762-2. http://books.google.com/books?id=x49nkF7HYncC., Chapter IX

- ↑ Lorentz, Hendrik Antoon (1895), Versuch einer Theorie der electrischen und optischen Erscheinungen in bewegten Körpern, Leiden: E.J. Brill

- ↑ Poincaré, Henri (1898/1913), "The Measure of Time", The foundations of science, New York: Science Press, pp. 222–234

- ↑ Galison, Peter (2003), Einstein's Clocks, Poincaré's Maps: Empires of Time, New York: W.W. Norton, ISBN 0393326047

- ↑ Poincaré, Henri (1900), "La théorie de Lorentz et le principe de réaction", Archives néerlandaises des sciences exactes et naturelles 5: 252–278. See also the English translation.

- ↑ Darrigol, Olivier (2005), "The Genesis of the theory of relativity", Séminaire Poincaré 1: 1–22, http://www.bourbaphy.fr/darrigol2.pdf

- ↑ Poincaré, Henri (1904/6), "The Principles of Mathematical Physics", Congress of arts and science, universal exposition, St. Louis, 1904, 1, Boston and New York: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, pp. 604–622

- ↑ Holton, Gerald (1988), Thematic Origins of Scientific Thought: Kepler to Einstein, Harvard University Press, ISBN 0674877470

- ↑ Einstein, Albert (1905), "Zur Elektrodynamik bewegter Körper", Annalen der Physik 322 (10): 891–921, doi:10.1002/andp.19053221004, http://www.physik.uni-augsburg.de/annalen/history/einstein-papers/1905_17_891-921.pdf. See also: English translation.

- ↑ Miller, Arthur I. (1981), Albert Einstein’s special theory of relativity. Emergence (1905) and early interpretation (1905–1911), Reading: Addison–Wesley, ISBN 0-201-04679-2

- ↑ Pais, Abraham (1982), Subtle is the Lord: The Science and the Life of Albert Einstein, New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-520438-7

- ↑ Minkowski, Hermann (1909), "Raum und Zeit, 80. Versammlung Deutscher Naturforscher (Köln, 1908)", Physikalische Zeitschrift 10: 75–88

See also

- Andromeda paradox

- Einstein synchronisation

- Hyperbolic-orthogonal

- Ehrenfest's paradox